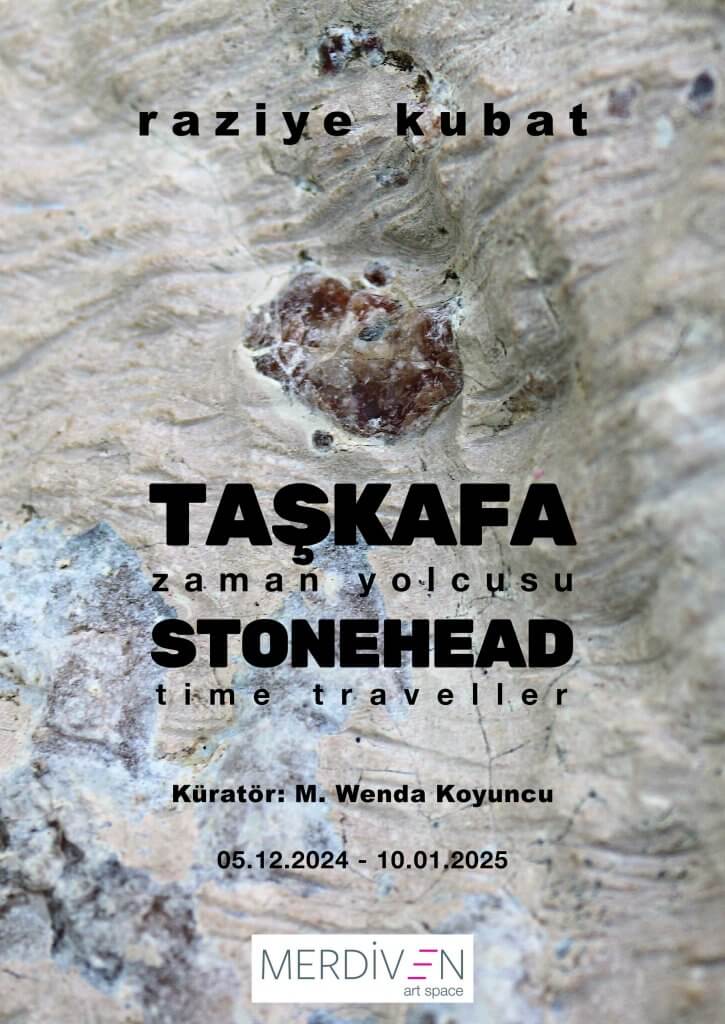

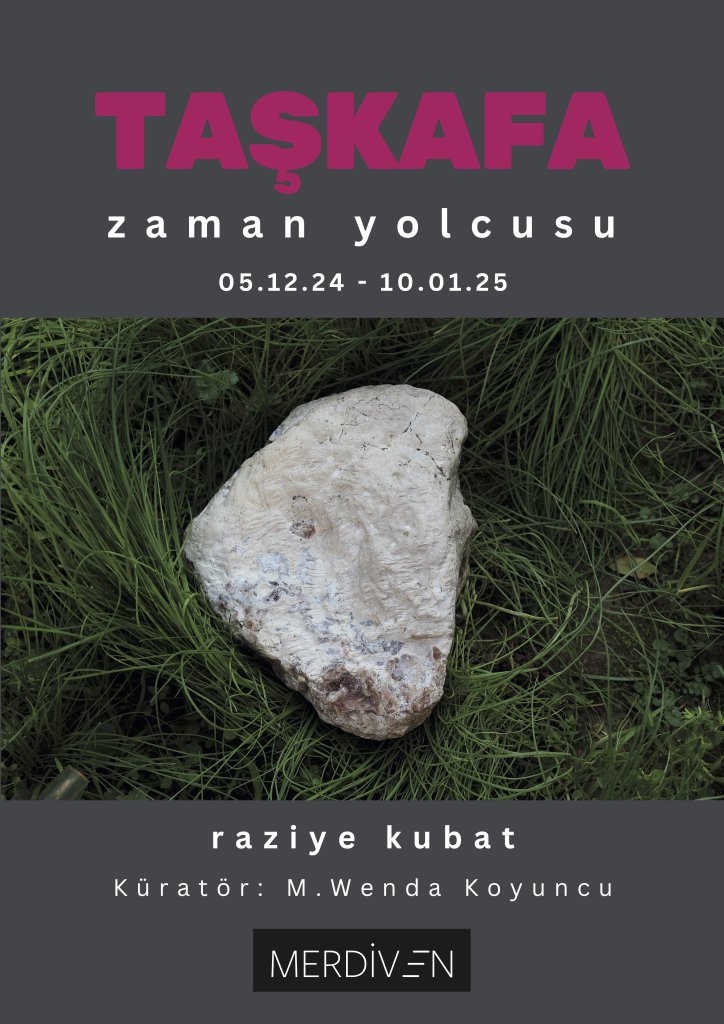

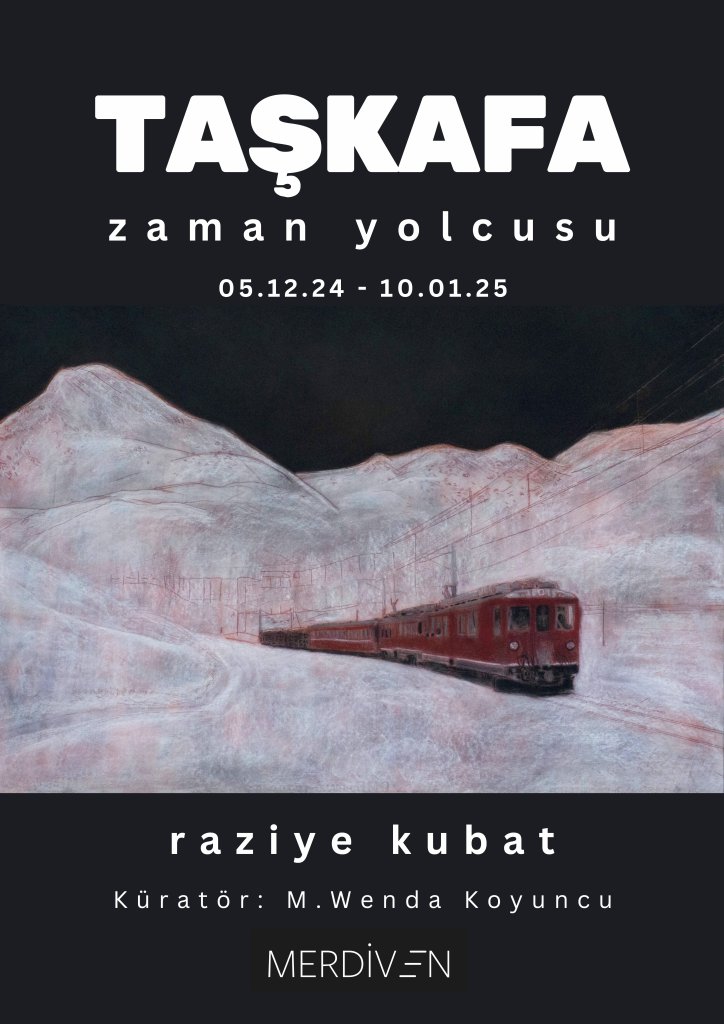

TAŞ KAFA – ZAMAN YOLCUSU

TAŞ KAFA – ZAMAN YOLCUSU

2021-2024

Broşür PDF: raziye kubat_brosur_taskafa_Low (1)

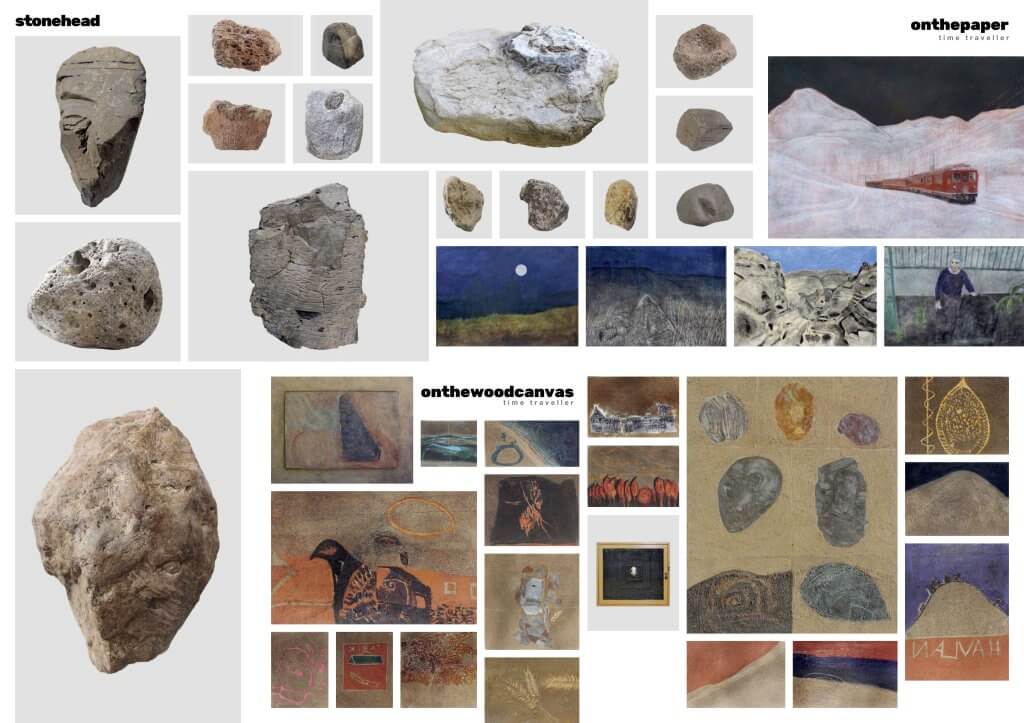

stonehead

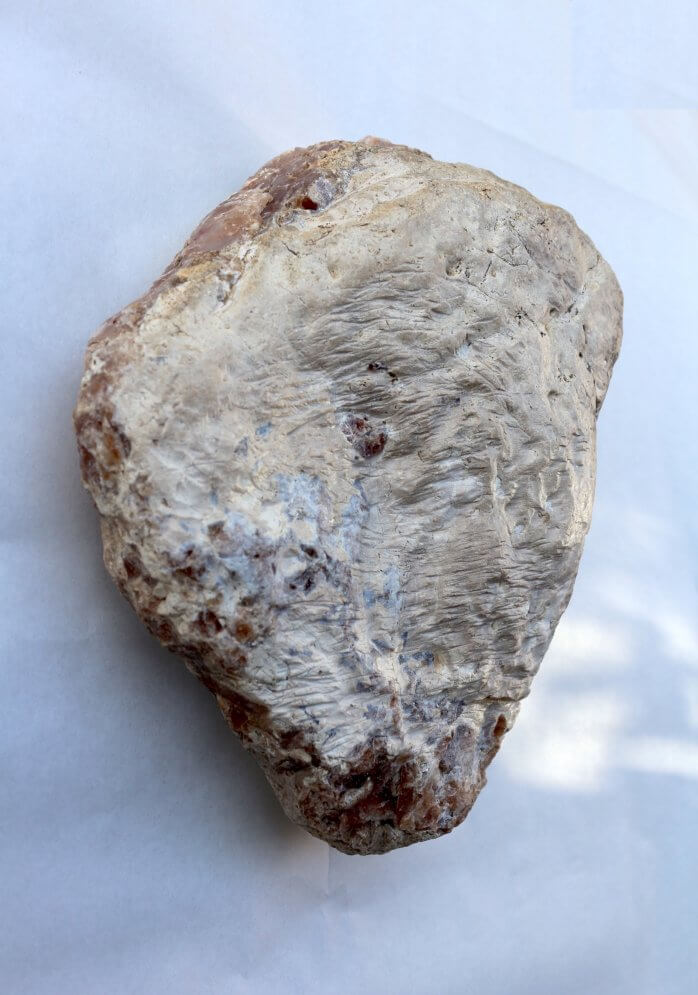

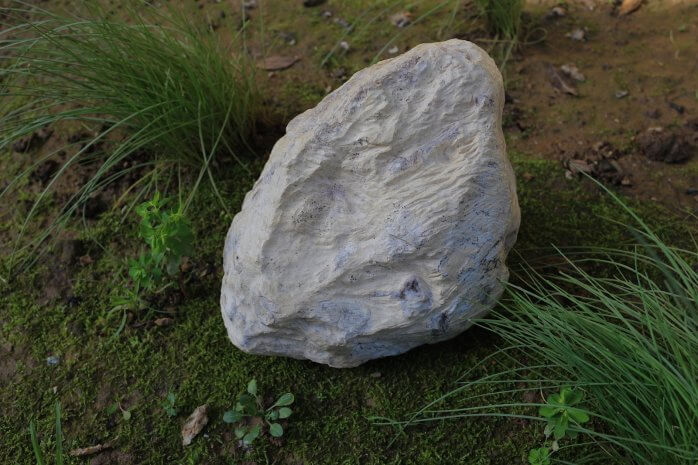

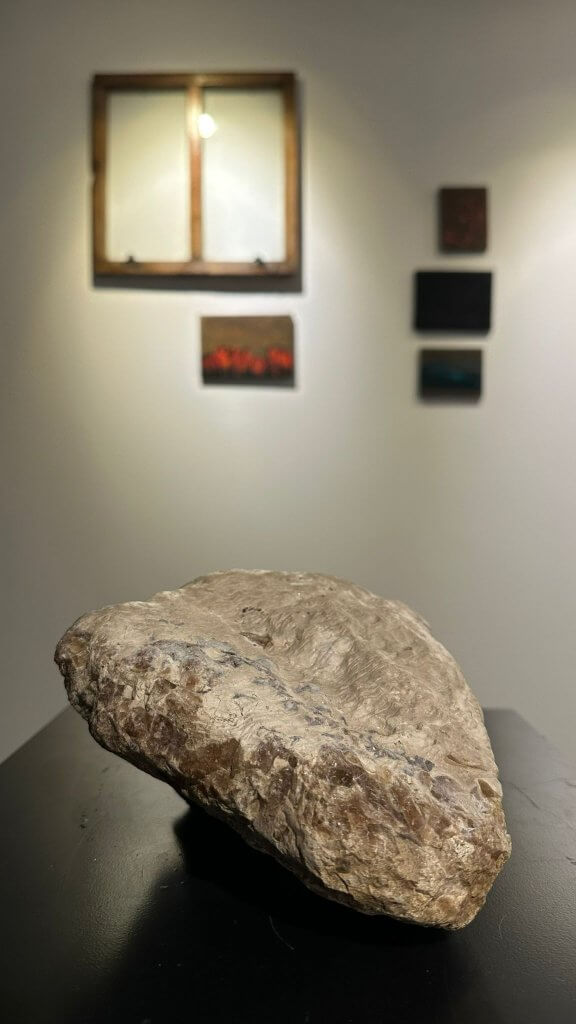

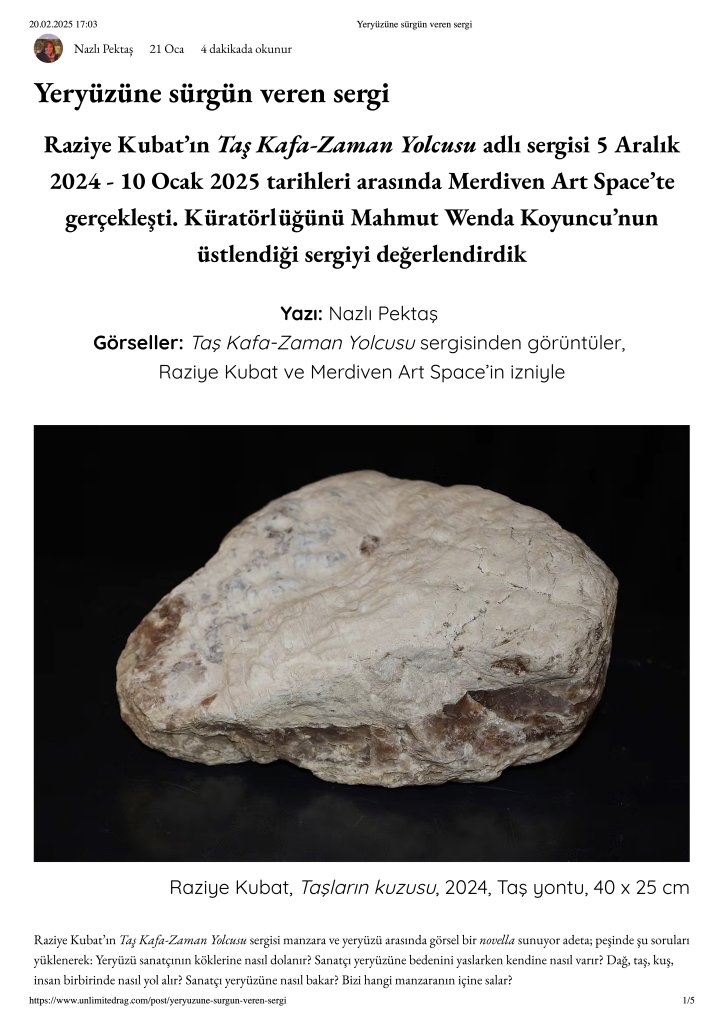

“lamb of the stones” hewn stone 25x40cm 2024

hewn stone

25x300cm

2024

t i m e t r a v e l l e r

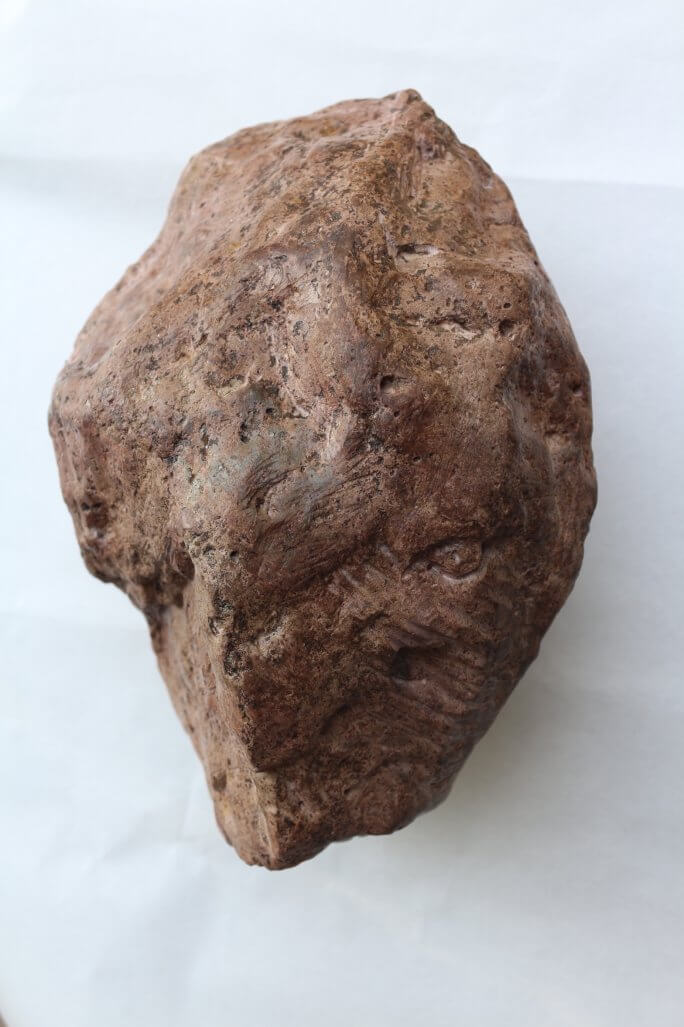

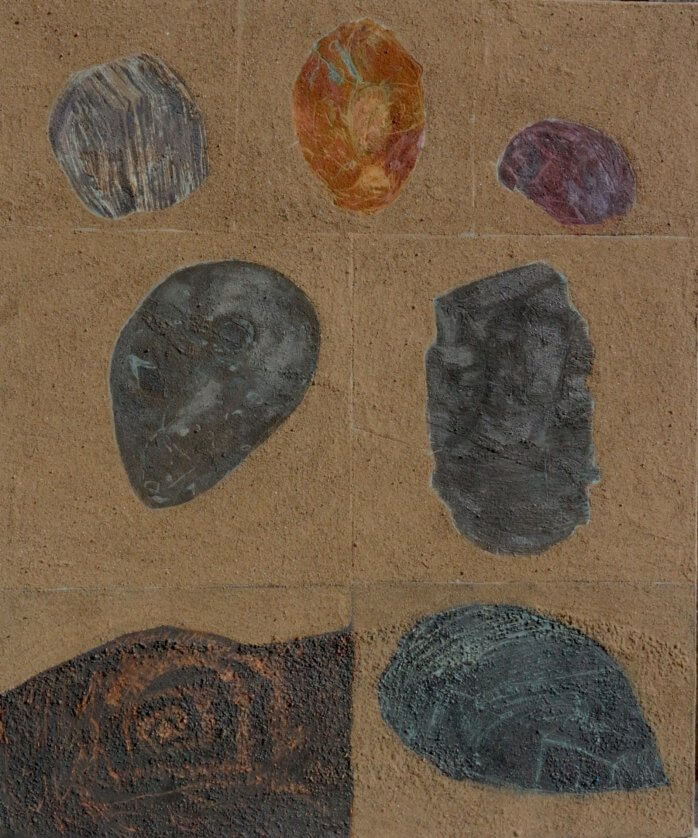

woman’s hand” 55×40 cm 2024

STONEHEAD KUMCAYURT SERIES

ONTHESAND

“KumcaYurt”

Kumcayurt Series

Sand and mixed media on the canvas.

120×90 cm 2024

Kumcayurt Series

“stonehead”

Sand and mixed media on the canvas.

120×100 cm

2024

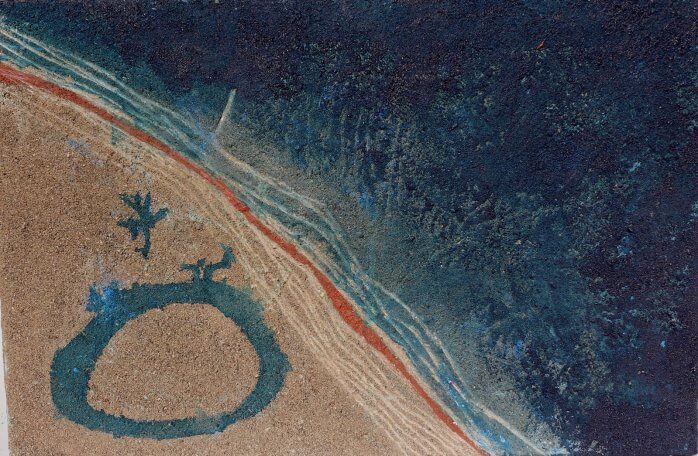

Kumcayurt Series

“stone of abundance”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

40×40 cm

2024

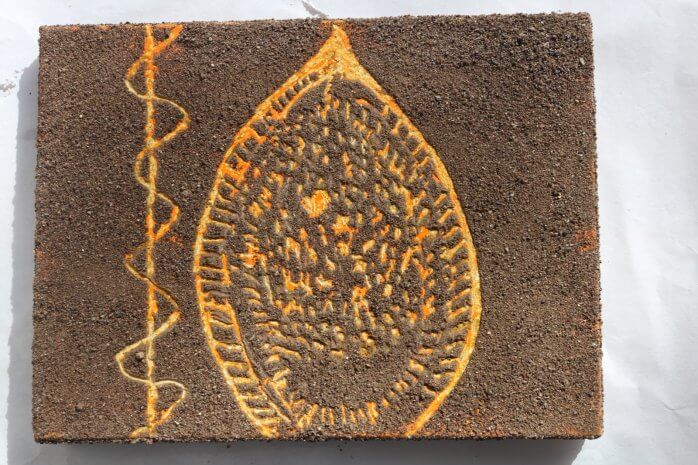

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-8”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

25×35 cm

2023

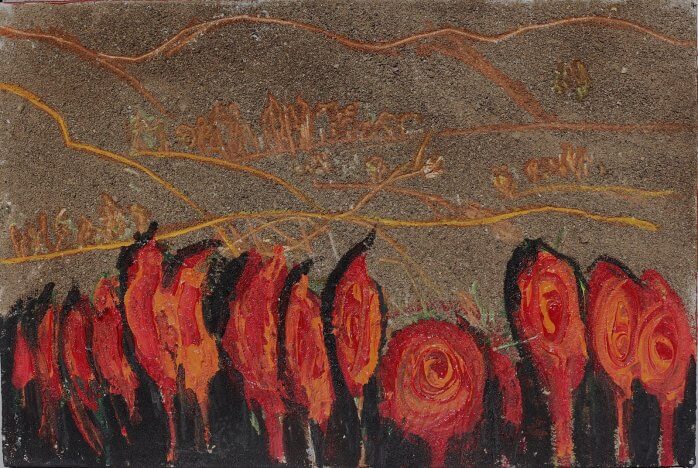

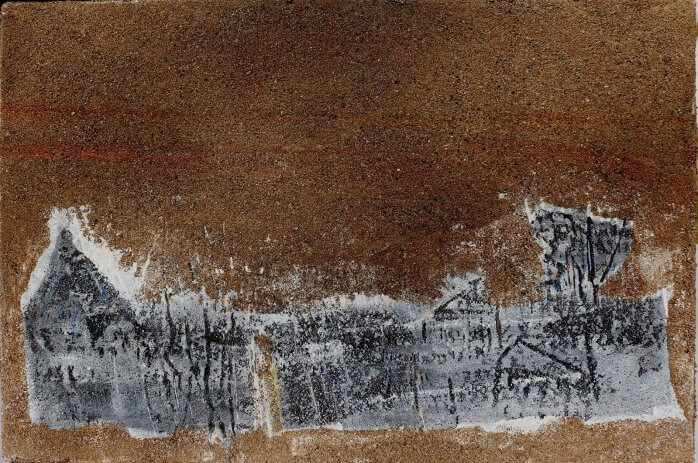

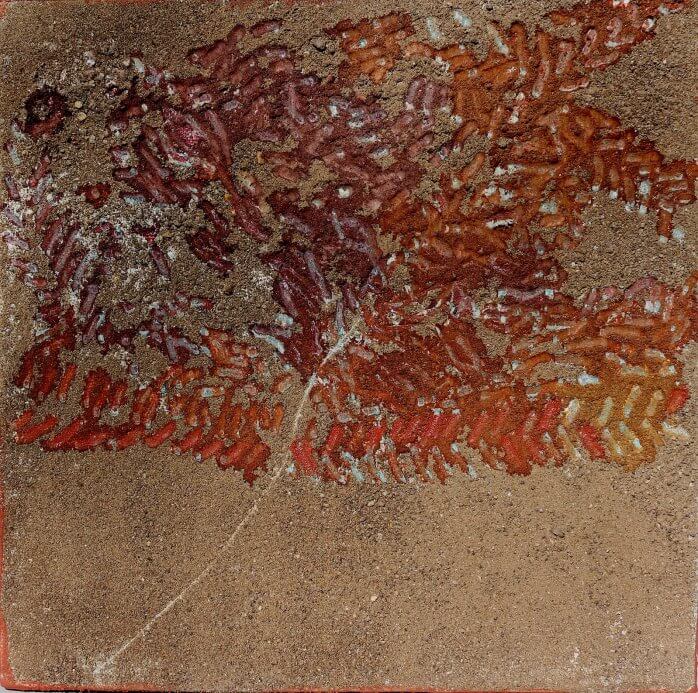

Kumcayurt Series

“red poplars”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

25×35 cm

2023

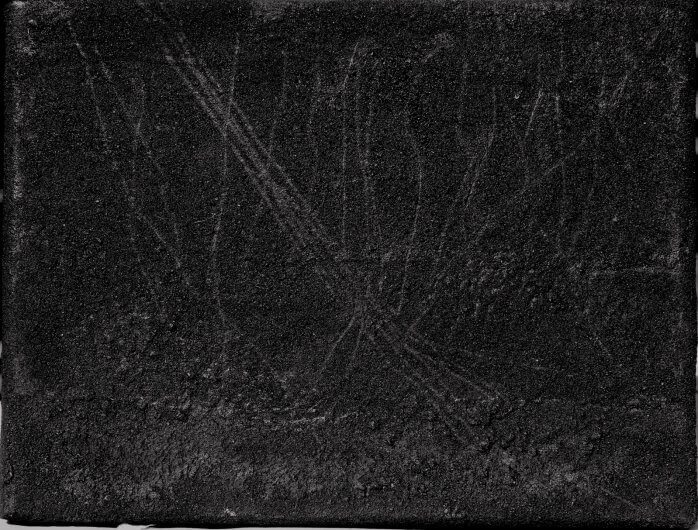

Kumcayurt Series

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

25×35 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

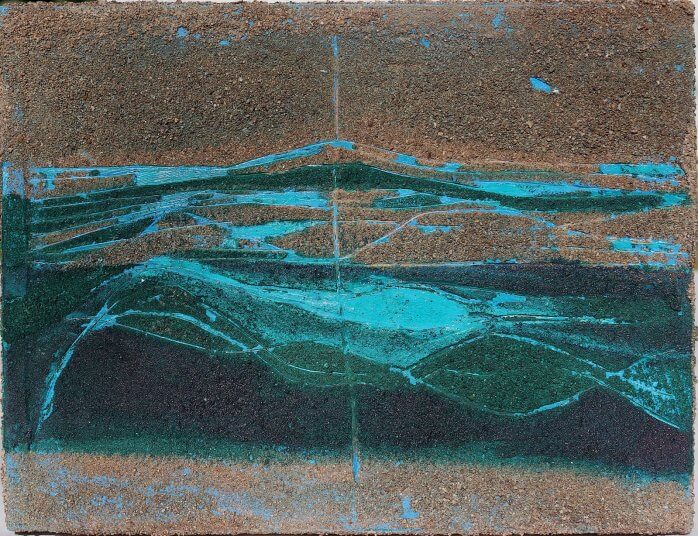

“genesis-1”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

” “genesis-2”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-3”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

genesis-4”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

15x20cm

2023

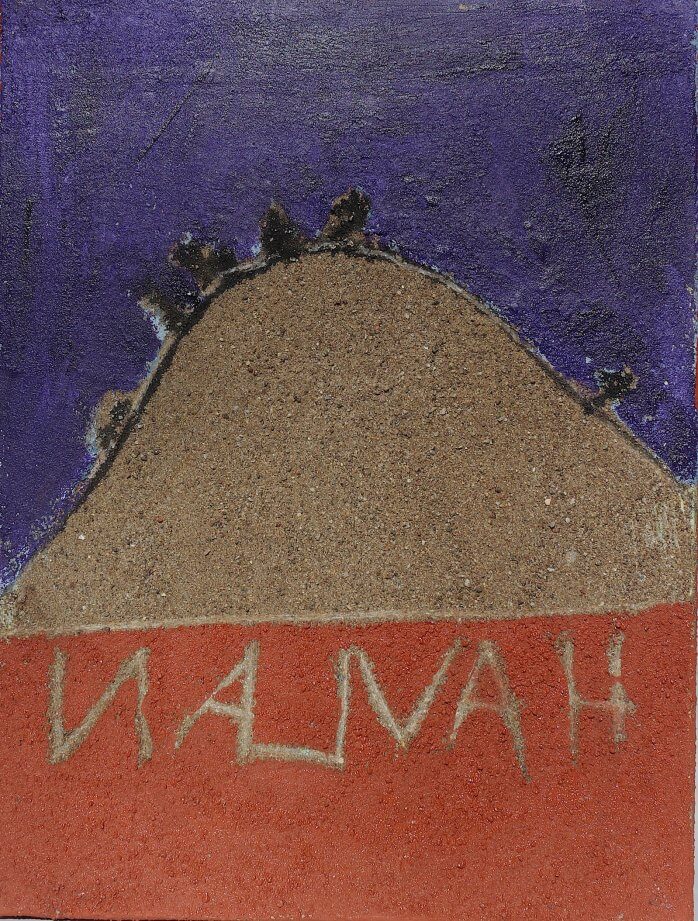

Kumcayurt Series

“havlan”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

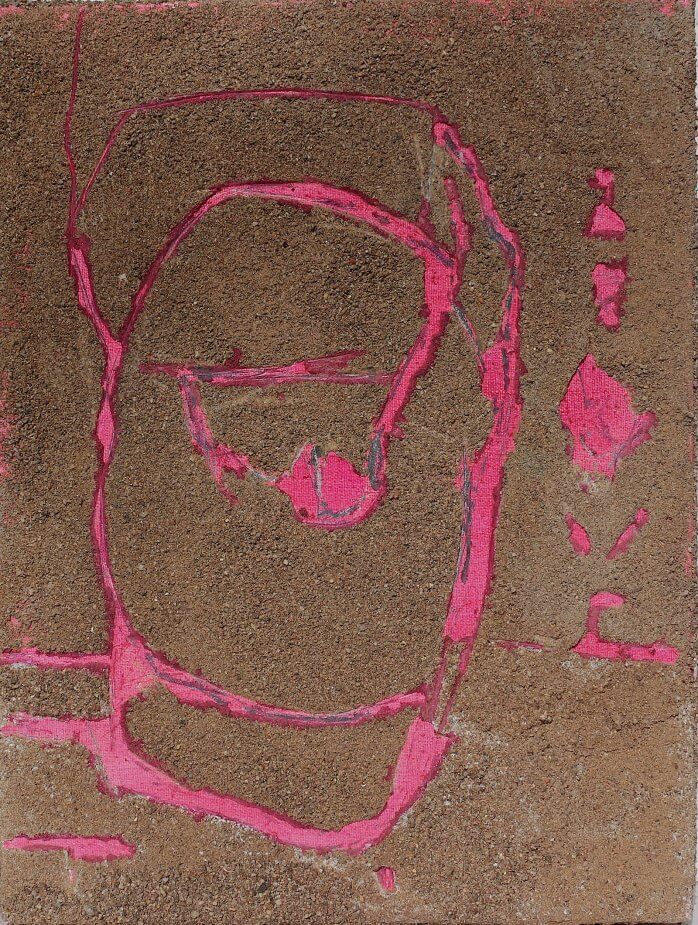

Kumcayurt Series

“pink zeyve”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

15x20cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-4”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

15x20cm

2023

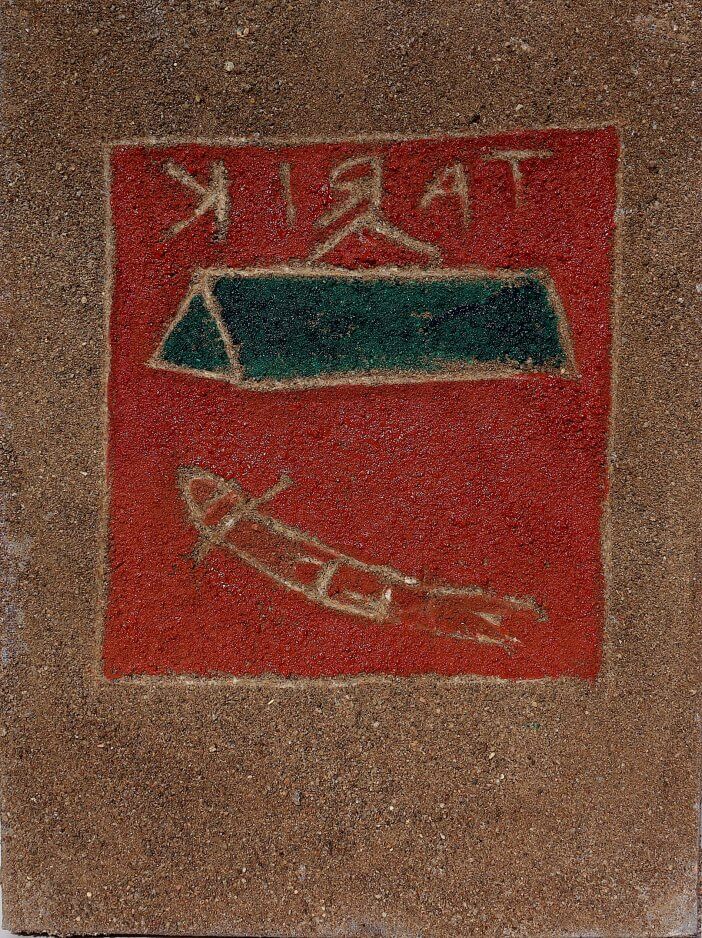

Kumcayurt Series

“tarık”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas. 15x20cm /2023

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-5”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-6”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm 2023

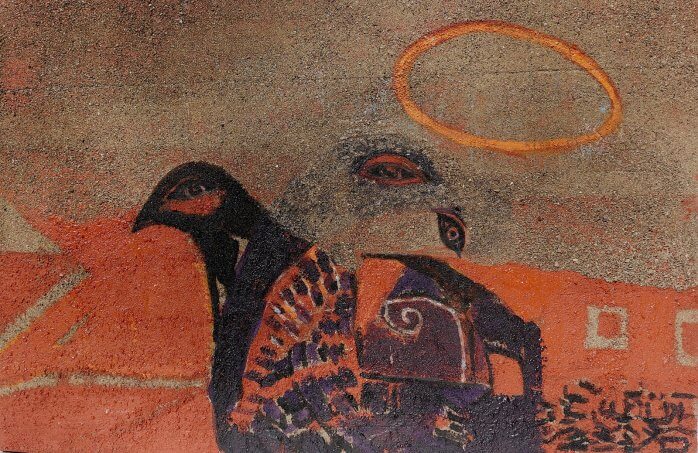

Kumcayurt Series

“talisman”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm 2023

Kumcayurt Series

“genesis-7”

Sand and mixed media on wood canvas.

20×30 cm

2023

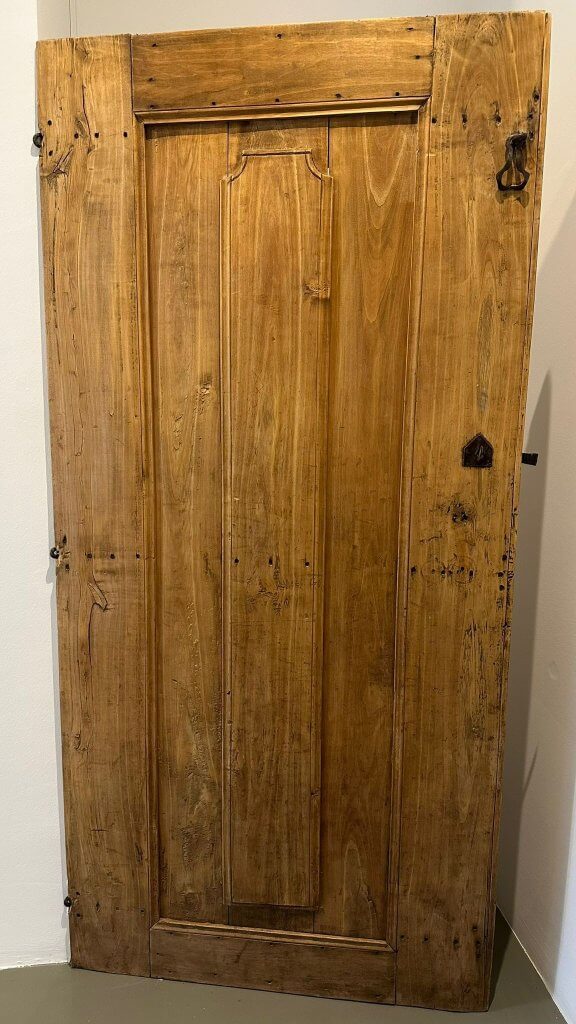

Timeless – Medium

65x58x8 cm

Sand into old wooden cabinet, snake upper jaw, mixed technique.

2024

ONTHEPAPER

Beginning

110×80 cm

Mixed technique on paper.

2022

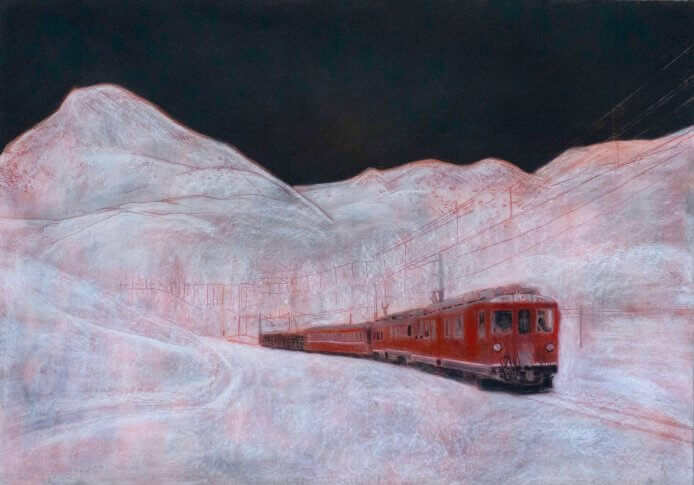

Time Traveler

110×80 cm

Mixed technique on paper.

2022

Kamışlıtarla

110×80 cm

Mixed technique on paper.

2022

Timeless

110×80 cm

Mixed technique on paper.

2022

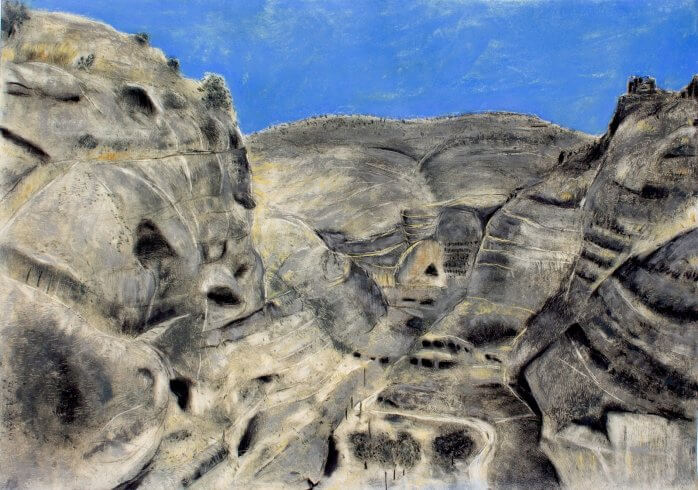

Zeyve

110×80 cm

Mixed technique on paper.

2022

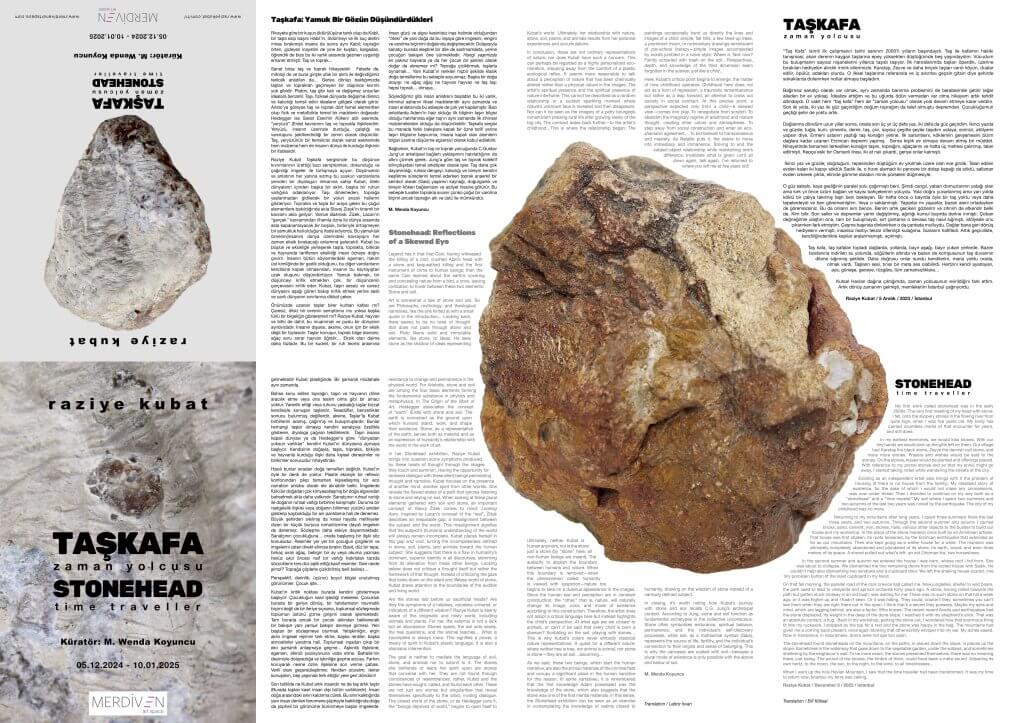

Stonehead: Reflections of a Skewed Eye

M.Wenda Koyuncu

Legend has it that that Cain, having witnessed the killing of a bird, crushed Abel’s head with a stone and bequeathed killing and the first instrument of crime to human beings; then the same Cain learned about the earth’s covering and concealing nature from a bird, a crow, leaving civilization to hover between these two elements: Stone and soil.

Art is somewhat a tale of stone and soil. So are Philosophy, mythology, and theological narratives, like the one hinted at with a small quote in the introduction…. Looking back, there seems to be no twist of thought that does not pass through stone and soil. Plato likens solid and immutable elements, like stone, to ideas. He sees stone as the shadow of ideas representing resistance to change and permanence in the physical world. For Aristotle, stone and soil are among the four basic elements forming the fundamental substance in physics and metaphysics. In The Origin of the Work of Art, Heidegger associates the concept of “earth” (Erde) with stone and soil. The earth is conceived as the ground upon which humans stand, work, and shape their existence. Stone, as a representative of the earth, serves both as material and as an expression of humanity’s relationship with the world in the work of art.

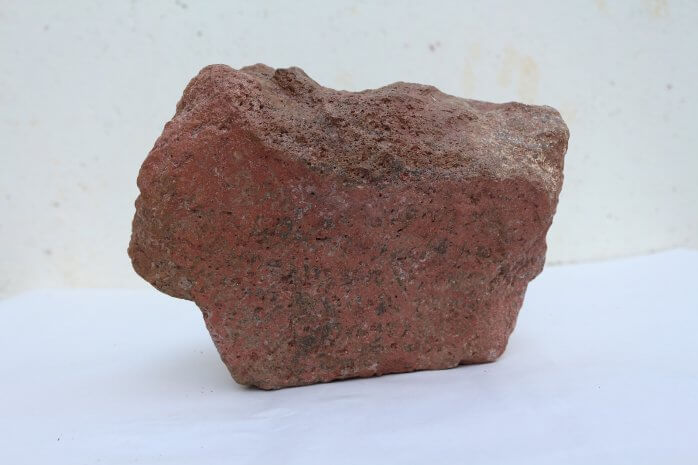

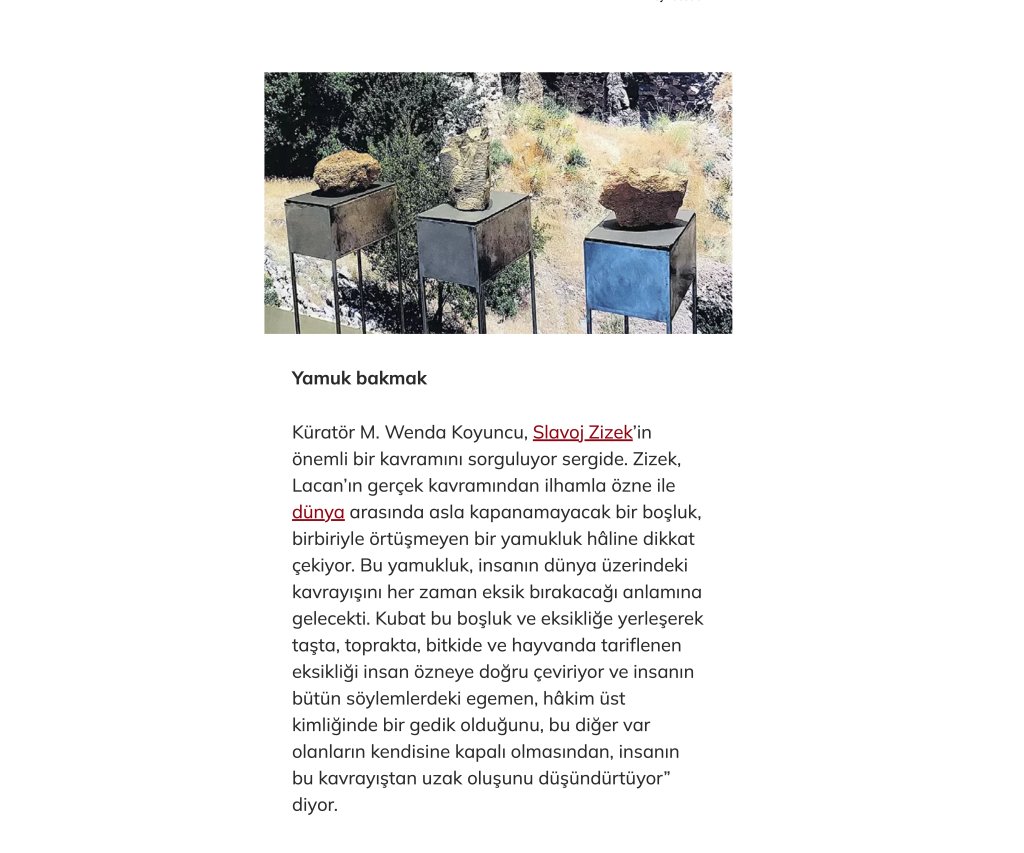

In her Stonehead exhibition, Raziye Kubat brings into question some symptoms produced by these twists of thought through the images they touch and summon. Having the opportunity for renewed dialogue with these silent beings permeating thought and narrative, Kubat focuses on the presence of another mind, another spirit from other worlds. She reveals the flawed states of a path that ignores listening to stone and relying on soil. When looking at these plural elements gathered with soil and stone, an important concept of Slavoj Žižek comes to mind: Looking Awry. Inspired by Lacan’s concept of the “real”, Žižek describes an irreparable gap, a misalignment between the subject and the world. This misalignment signifies that the subject’s (human’s) understanding of the world will always remain incomplete. Kubat places herself in this gap and void, turning the incompleteness defined in stone, soil, plants, and animals toward the human subject. She suggests that there is a flaw in humanity’s dominant, superior identity in all discourses, stemming from its alienation from these other beings. Looking askew does not critique a thought itself but rather the framework of that thought. Instead of criticizing the gaze that looks down on the silent and lifeless world of stone, Kubat draws attention to the boundaries of the audible and living world.

Are the stones laid before us sacrificial heads? Are they the symptoms of a helpless, voiceless universe, or indicators of a different wisdom? Raziye Kubat is keenly aware of this enigmatic and misty world, including animals and plants. For her, the external is not a lack but an abundance. Stones speak, the soil acts wisely, the tree questions, and the animal teaches… What is incomplete is always more. This signifies a power, a theory of spirit in Kubat’s plastic language. It is also a shamanic intervention.

The goal is neither to mediate the language of soil, stone, and animals nor to submit to it. The stones she befriends or leans her spirit upon are stones that converse with her. They are not found through coincidences or resemblances; rather, Kubat and the stones have sought, called, and found each other. These are not just any stones but singularities that reveal themselves specifically to the artist, inviting dialogue. The closed world of the stone, or as Heidegger puts it, the “beings deprived of world,” begins to open itself to Kubat’s world. Ultimately, her relationship with nature, stone, soil, plants, and animals results from her personal experiences and accumulations.

In conclusion, these are not ordinary representations of nature, nor does Kubat have such a concern. This can perhaps be regarded as a highly personalized eco-narration, stepping away from the comfort of a plastic ecological reflex. It seems more reasonable to talk about a perception of nature that has been chemically altered rather than a physical nature in the images. The artist’s spiritual presence and the spiritual presence of nature intertwine. This cannot be described as a random relationship or a sudden sparkling moment where nature’s unknown face is revealed and then disappears. Nor can it be seen as the imagery of a petty bourgeois romanticism praising rural life after growing weary of the big city. The contract dates back further—to the artist’s childhood…This is where the relationship began. The paintings occasionally hand us directly the lines and images of a child: simple, flat hills, a few lined-up trees, a prominent moon, or rudimentary drawings reminiscent of pre-school literacy—simple images accompanied by words jumbled in a naive style: Where is Tarık now? Faintly scrawled with trash on the soil…Perspectives, depth, and knowledge of the third dimension seem forgotten in the scenes: just like a child…

Here, Kubat’s critical point begins to emerge: the matter of how childhood operates. Childhood here does not act as a form of regression, a traumatic rememberance but rather as a leap forward, an attempt to cross out society in social contract. At this precise point, a perspective expected only from a child—a skewed view—comes into play. To renegotiate from scratch. To abandon the imaginary regime of adulthood and mature thought, creating other colors and atmospheres. To step away from social construction and enter an eco-shamanic agreement… To bid farewell to transcendence and mastery. As Bataille puts it, the desire to move into immediacy and immanence. Striving to end the subject-object relationship while maintaining one’s difference. Invalidate what is given: Let’s sit down again, talk again, I’ve returned to where you left me at five years old!

Ultimately, neither Kubat is human anymore, nor is the stone just a stone (by “stone” here, all non-human beings are meant). The audacity to abolish the boundary between humans and nature. When this boundary is removed—when the phenomenon called humanity is viewed with suspicion—nature too begins to take on a dubious appearance in the images. Since the human eye and perception are in constant construction, the “other,” that is, nature, will naturally change its image, color, and mode of existence according to this construction. Therefore, the artist does not adopt a critical language here but instead highlights the child’s perspective. At what age are we closest to animals, or can’t it be said that every child is born a shaman? Scribbling on the soil, playing with stones… This is why Kubat’s colors never embody classical nature representations. A quest for a different nature: where neither tree is tree, nor animal is animal, nor stone is stone—they are all soil…becoming…

As we said, these two beings, which start the human narrative, are also the primal materials of the criminal field and occupy a significant place in the human narrative for this reason. In some narratives, it is remembered that the first knowledge Adam possessed was the knowledge of the stone, which also suggests that the stone was one of the first mental materials. In this sense, the Stonehead exhibition can be seen as an exercise in contemplating the knowledge of realms closed to humanity, drawing on the wisdom of stone instead of a narrowly defined subject.

In closing, it’s worth noting how Kubat’s journey with stone and soil recalls C.G. Jung’s archetypal context. According to Jung, stone and soil function as fundamental archetypes in the collective unconscious. Stone often symbolizes endurance, spiritual balance, permanence, and the individual’s self-discovery processes, while soil, as a matriarchal symbol (Gaia), represents the source of life, fertility, and the individual’s connection to their origins and sense of belonging. This is why the canvases are coated with soil—because a plural mode of existence is only possible with the above and below of soil.

Translation / Lebriz İsvan

StoneHead / Time Traveller

My first work called stonehead was in the early 2000s. The very first meeting of my head with stone: I fell, onto the slippery stones in the flowng river from quite high, when I was five years old. My body has carried countless marks of that encounter for years, and still does.

In my earliest memories, we would kiss stones. With our tiny hands we would pick up the gifts left on them. Our village had Karataş the black stone, Zeyve the dervish cell stone, and many more stones. Prayers and wishes would be said to the stones. On the stones, kisses would be planted and offerings placed. With reference to my primal stones and so that my ennui might go away, I started taking notes while wandering the streets of the city.

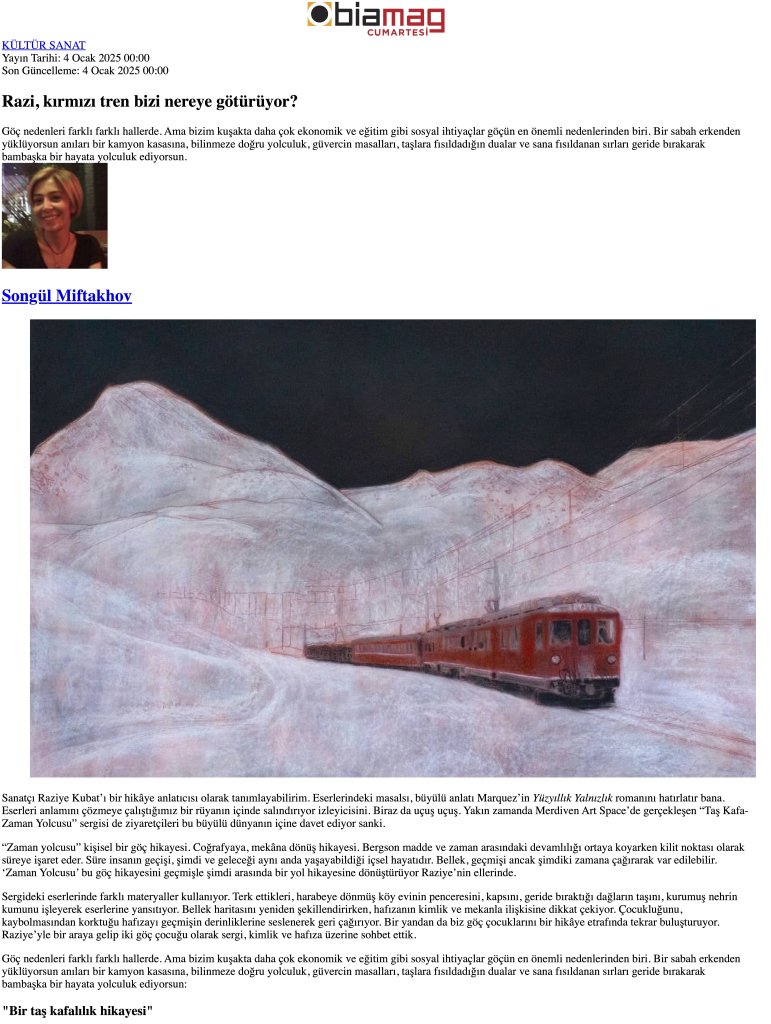

Existing as an independent artist also brings with it the problem of housing (if there is no house from the family). My idealised story of existence, for the sake of which i would not make any concessions, was now under threat. Then I decided to continue on my way both as a ”stonehead” and a ”time traveler”.My soil where I spent two summers and two autumns of the last two years was ruined by the earthquake. The city of my childhood was no more.

Returning to my mountains after long years, I spent three summers there the last three years, and two autumns. Through the second summer and autumn I carried bricks, sand, cement, iron, stones, nails, various other objects to the builder to build our house and my workshop. In the place of the stone mansion once built by an Armenian artisan. That house was first shaken, its roots loosened, by the Erzincan earthquake that extended as far as our mountains. Then she kept going as a winter house for a while. The mansion was ultimately completely abandoned and plundered of its stone, its earth, wood, and even three meters of its space. A shovel pulled out what’s left- an old Ottoman lira, two horseshoes.

In the second summer and autumn we entered the house I was born, whose roof I fell from. She was about to collapse. We dismantled the two remaining doors from the looted house with Sadık. He couldn’t help also dismantling two windows and a cupboard door. We left the shaking house scared, one tiny porcelain button of the inset cupboard in my hand.

On that fall morning, the parallel road of the rock crevice had called me. Now junglelike, shelter to wild boars, the path used to lead to vineyards and apricot orchards forty years ago. A stone, having rolled towards the path but gotten stuck midway in an old bush, was waiting for me. There was no such stone on that hill a week ago, or it was higher up and I hadn’t seen. Or it was hiding. They could, couldn’t they, sometimes you can’t see them when they are right there out in the open. I think that’s a secret they possess. Maybe my eyes and mind, which are lagging behind, are also a factor. Who knows. The recent recent floods and earthquakes had the stone displaced, its weight in the deep of the dune slope. I reached it with my shepherd’s stick. That was an absolute contact, a hug. Back in my workshop, getting the stone out, I wondered how that enormous thing fit into my rucksack. I stopped by the tap for a rest and the stone was happy in the bag. The mountains had given me a coming back present, once again blowing that otherworldly whisper into my ear. My aches eased. Now in transience, in naturalness, doors were not ajar but open.

The stonehead found stoneheads on the mountains, on the paths, in places down the slope, in places up the slope. Sometimes in the waterway that goes down to the vegetable garden, under the willows, and sometimes sheltering by the neighbour’s wall. To be more exact, the stones presented themselves. there was no meaning there, just being. The sound of the stones, the timbre of them, could have been a meta-sound. Adjusting its own hertz, to the moon, the sun, to the night, to the wind, to all timelinesses…

When I went up the holy Havlan Mountain, I saw that the time traveller had been transformed. It was my time to return now, İstanbul my terra was calling.

Raziye Kubat / December 5 / 2023 / Istanbul

Translation / Elif Köksal

” ramblings of a farmhand under the sun”

VİDEO

timetraveller-stonehead

“güneşte ırgatın sayıklamaları – ramblings of a farmhand under the sun”

“03 minute:38 second”

2024

Video Link: https://vimeo.com/1035209530?ts=0&share=copy&fbclid=IwY2xjawIkC5JleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHSWULAvzcKlQhL5XNLYa-xerdsQk9QlUnXytaYoZDM8Cby5yDqLBAik10A_aem_AGv3VH7MEOisDEWHP4g_fw

Sergi Söyleşisi: “Gerçekliğin Cevheri Üzerine” Raziye Kubat’ın M. Wenda Koyuncu küratörlüğünde gerçekleşen “Taş Kafa-Zaman Yolcusu” isimli sergisi kapsamında düzenlenecek söyleşi, sanat tarihçisi Seda Yavuz ve sanatçının katılımı ile birlikte 3 Ocak Cuma günü saat 17.00’de Merdiven Art Space’de gerçekleşti.

Kamera – Video Kurgu: Sinan Eren Erk

Söyleşiye katılan ve destekleyen herkese teşekkür ederiz.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKECrP3NmdI

FROM EXHIBITION

STONEHEAD – TIMET RAVELLER

MEDYA REPORTS

(Some articles and interviews in the press)

https://artdogistanbul.com/bagimsiz-sanatci-olmak-yoksunluk-mu-ozgurluk-mu-raziye-kubat/

https://bianet.org/print/haber/razi-kirmizi-tren-bizi-nereye-goturuyor-303308

https://www.unlimitedrag.com/post/yeryuzune-surgun-veren-serg

https://www.unlimitedrag.com/post/yeryuzune-surgun-veren-serg

https://www.milliyet.com.tr/kultur-sanat/taslar-soyler-sana-sustugunu-7260116

https://argonotlar.com/koyde-ev-sehirde-atolye/vc_row]